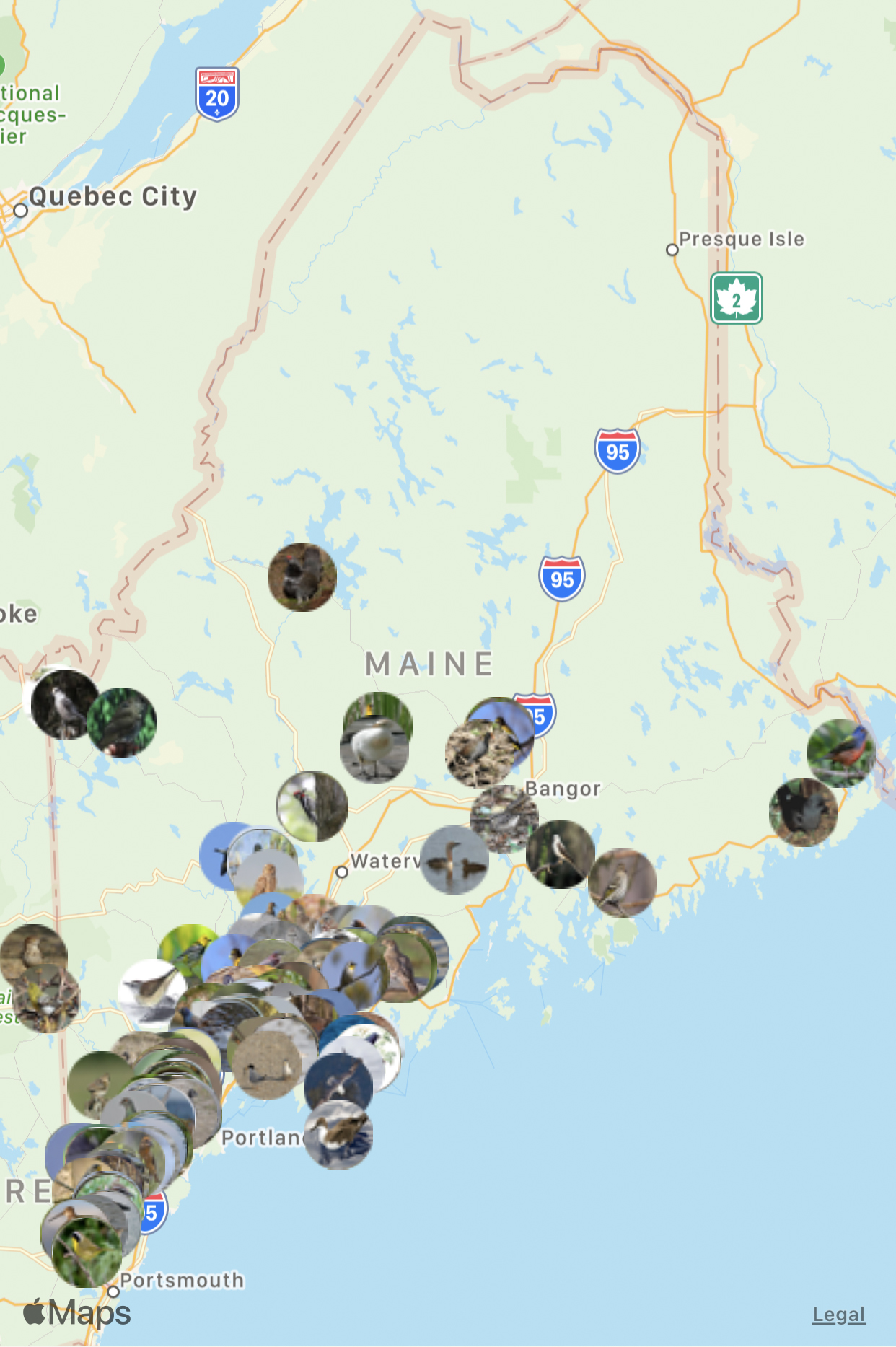

It’s the beginning July and we’re at the halfway point of my Maine Big Year . . . six months to go.

Bird #1 was an hour before sunrise on New Years Day . . . a Great Horned Owl calling at the Grange Hall Parking Lot in Cape Elizabeth.

Bird #286 was June 30th . . . a Spruce Grouse standing in the middle of a defunct rail road bed near Moosehead Lake.

The State Record of 317 which was set in 2017 by Josh Fecteau is possible but will require a lot of effort and perhaps even more luck.

One would think thirty-one more birds over six months would be quite simple . . . but all the easy birds . . . the Bluejays and Mourning Doves were picked up long ago.

At the end of July and into the fall . . . we will see shorebird migration . . . sandpipers and related species moving south from their Arctic nesting areas. This migration is slow with birds stopping to feed (often at the beach) for weeks at a time before continuing south. I should be able to pick up at least five to eight new birds during this migration.

Then there are the sea birds . . . countable within 20 miles of the Maine Coast. Ingrid and I currently have six “pelagic” trips scheduled thru October and we hope to identify eight or nine or the regular offshore visitors.

Finally there are a couple rare birds that I know about that will require long drives into the Maine north woods or long paddling excursions on Maine lakes.

If we get all these birds, we’ll still be about 15 or more short of the record.

Here is where we count on something called “post-breeding dispersal”.

After a Mommy and Daddy bird raise their young, its not uncommon for one of the parents (and sometimes their young) to launch into a long, seemingly random migration flight searching for food. In late summer and into the fall, birds from the south and mid-west may show up in Maine (I hope) thousands of miles from their normal ranges. Or at least that has happened in the past. There is no way to plan for it. . . . but one has to be ready to drop everything and break a few traffic laws . . . before the rarity flies away.

Finally there are hurricanes . . . a big tropical storm moving up the east coast can sweep thousands of birds up and deposit them in places that they don’t belong. For instance in 2019, Black Skimmers, a bizarre looking seabird normally found in the Gulf of Mexico started appearing on the beaches of Maine. They had been blown up to Nova Scotia by a hurricane and were moving back home.

I’m not sure its good karma to wish for lots of hurricanes to sweep up the east coast . . . but it sure would help.

Anyway, the next six months of the Maine Big Year will be very different from the first six months. Gone are the days of six new birds in one morning . . . from now on one or two new birds a week will be a good one.